A Filmmaker’s Toolbox: The Camera

SynopsiTV is about bringing good entertainment to each and every individual. We strongly believe that you are entitled to your own opinion about film and TV, and that you do not need to rely on ‘experts’ or your friends. After all, nobody can judge your experience but you. So here on our blog we are featuring an expert, not to tell you what to like, but to explain aspects of filmmaking so you are better equipped to make and defend your ratings and opinions. Enjoy.

Every filmmaker has a toolbox of techniques to choose from while making a film. The tools of filmmaking are used to the communicate intellectual and emotional information the director wants to convey. Filmmakers use the tools in many different ways to communicate their messages.

Some directors apply the same style and techniques to every film (like described in our blog on director Wes Anderson), despite differences in the projects. This could be for a number of reasons; their desire to allow the material to speak louder than the techniques, to draw comparisons between different films, or maybe the belief that technique should emanate from the author of a given work, not the material. Or it could just be unconscious.

But many filmmakers employ different techniques based on the needs of each individual project (narrative, tone, themes, etc.). One tool (say, a certain camera movement) will be used differently by different filmmakers project-to-project. The same tool can even be used to different ends by the same filmmaker project-to-project or within the same film.

No matter how they’re used or the intentions behind their use, the tools themselves remain the same for all filmmakers. Let’s take a look into the filmmaker’s toolbox.

Here’s a basic overview of the filmmaker’s tools: Light, Camera (frame size, angle, duration, movement or lack thereof, composition, and depth of field), Casting (performance and type/style), Production Design (sets, props, costumes, and locations; colors, styles, etc.), Sound Design, and Music. I didn’t include tools associated with writing or crafting a story, which is something that most directors will do even if they aren’t credited screenwriters on a project. But those tools are very important as well.

Mostly, these tools fall into the hands of the director. But unless the director is multi-talented and overly controlling or working with a prohibitive budget, a number of people will be in charge of executing the vision of the director. It’s important to note, however, that even though the director may not be operating the camera, painting the sets, recording the sound effects, or composing the score her or him self, all of these elements are very much dictated and guided by the vision of the director. The director will normally be very involved in the decision making in each field.

All of these tools are integral, but because one of the more apparent signatures a director will leave on a film is the way the camera is employed, let’s focus on the Camera and its individual elements.

The Camera

The camera is used to create shots. A shot is the building block of all visual media storytelling—there is no movie, TV show, webisode, commercial, music video, etc. without shots. Without shots, it’s radio.

Each shot consists of six pieces: frame size, angle, duration, movement or lack there of, composition, and depth of field.

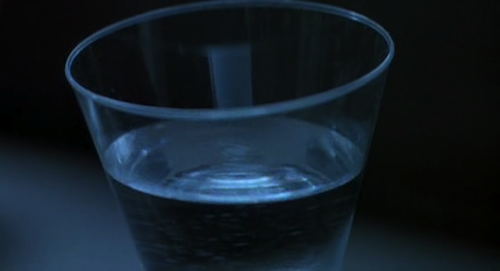

Frame size is usually discussed as shot type—close up, medium shot, wide shot. The shot in Jurassic Park of the glass of water shaking as the T-Rex approaches…

…that’s a close up shot (maybe even an extreme close up; this language can be a little subjective). The frame’s size (determined by the camera/lens position and its relation to the object on screen), while technically always the same size on the screen you’re looking at, changes in relation to the object being filmed (the size of that object within the frame).

Angle is perspective. There are three perspectives that the camera can take in relation to what it is filming: low angle (looking up at the subject/below the eyes), eye level (being even with the subject), and high angle (looking down at the subject/above the eyes).

You’ll often see angle used most starkly in point of view shots (POV), for example when a character looks up and realizes a monster is about to devour them - the angle is meant to mimic the POV of the monster.

The duration of a shot is the length of its take as it appears in the finished film. A take is one shot from the moment the camera begins rolling until the moment the camera stops. It doesn’t matter if the camera moves or the angle changes. Directors will use varying ‘take durations’ depending on the needs of a scene or film. For example, Gus Van Sant employs long duration takes (with a camera that tracks behind his characters) in Elephant…

…to, in my opinion, encourage us to shed our normal pacing expectations and to really borough into the experiences, lives, and emotions of the main characters. He wants us to hear what they hear; to feel what they feel; to experience their average, mundane lives moment to moment - without a lot of the traditional artifice of filmmaking - as they walk down the long, dark, lonely high school hallways. In contrast, Baz Luhrmann uses extremely short takes (and thus lots of rapid cutting) in the frenetic performance sections of Moulin Rouge (check out the trailer).

A moving camera can have a very different effect than a stationary camera. It should never be assumed that a camera should be stationary by default and only move for a reason. There should also be a reason if the camera is kept stationary. The motivation is rooted in the story, theme, tone, intentions, etc., so movement or the lack of movement of the camera must be carefully considered.

Composition is the way in which objects and subjects are arranged in the frame in relation to each other, the edges of the frame, and the camera. Placing subjects in the foreground (close to the camera), the midground, or the background (far from the camera) is a common way a director will take advantage of composition.

One of the best examples of this might be towards the end of Alien when Ripley is in the small escape pod. Having believed she has escaped all danger, Ripley has undressed and is preparing the ship for her space sleep.

The film cuts to a medium shot with Ripley in the foreground hugging the left of the frame and the black machinery of the ship is in the background filling the right side of the frame. The frame is smaller and the choice of a longer lens (and thus a shallower depth of field) compresses the image, so the distance between the foreground and background is minimal.

We don’t realize it yet, but the focal point of the shot is an alien that is hiding in the wall. As Ripley moves left to right across the screen, the alien’s hand shoots down from the wall—scaring both Ripley and us.

Ridley Scott, in composing the shot, takes full advantage of the different planes and both uses a tried and true trope of horror films - having something on a different plane in the shot appear to scare the character and audience - and upends the trope by having the alien disguised in the frame from the moment the shot begins.

Finally, depth of field. To keep it simple (especially because this stuff still can confuse me), depth of field is the distance between the nearest and farthest objects that appear in focus and is determined by the director’s choice of lens. A wider lens will allow more to be in focus while a longer lens allows for a narrower part of the frame to be in focus. The lens size (a wide angle lens vs. a telephoto lens, for example) not only determines how much will be in focus but also how much can be seen in a single frame (one window on a skyscraper through a telephoto lens or the whole skyscraper through a wide angle lens) and how things will look and feel. Longer lenses tend to compress the image while wider lens tend to expand the image. A moving camera with a long lens will often make the image feel more shaky and frenetic.

To return to the Alien example, a longer lens is used in the shot, so not only do the foreground and background feel closer together, but the background is also a smidge out of focus. When the alien’s hand pops into frame, it enters on the same plane that Ripley is on, so it’s crisply in focus, adding to the jolt of its sudden appearance.

How to use the camera tool comes down to what the filmmaker is trying to communicate and what certain effect she or he is trying to achieve.

These determinations often arise from the narrative, point of view (of director, character, audience, etc.), and/or emotion (of the scene, of character(s), etc.). The director may use the camera to dictate information, emphasize, or establish rhythm. To come to their choices they analyze the script, ask “what needs to be communicated, narratively and emotionally?,” and then determine which shot/angle/movement/lens best communicates those things. Or the decision may be purely instinctual. Filmmakers will also often build a shot strategy for an entire film or for an individual scene or scene-sequence to ensure coherence and consistency.

Why should you care?

For aspiring filmmakers and diehard fans, the best way to learn more about filmmaking is to watch films with an analytical eye. Think about the tools that a filmmaker has at her or his disposal and apply them retroactively to any given movie: what did I notice about that scene? Why would the director make the choices he or she did? Was it effective? What was the motivation for that choice? You might never know the director’s reasoning, but that doesn’t matter.

Any piece of art becomes ours as soon as it’s put out into the world. An artist will have intentions and they are either effective or ineffective at communicating those intentions.

Your interpretations are valid, though others may disagree with them. Watch films, analyze them based on what their intentions are and whether or not they work (not whether or not you like the film, that’s never a suitable means for analysis or critique), and then have a discussion, even if it’s just with yourself (but better on SynopsiTV), articulating your thoughts on the film.

Doing this has become such a habit for me that the sentences start coming to me as I’m still watching the film and my mind mulls over them, reshapes them, finds evidence to support or challenge my critiques. So by the end of the film I’m ready to present my analysis, or at least my gut reaction. I’ve found this exercise tremendously helpful in not only forming my critical thinking skills but also in honing my writing and storytelling skills, and I think you’ll find the same thing to be true.

So you may not have the equipment you need to go out and make films, but your journey towards becoming a filmmaker (or just a very astute fan) starts with watching films, analyzing them, and learning how to speak the cinematic language. With this overview of the filmmaker’s tools and an in depth look at the camera tool, you’re ready to begin.

Emmy-award winning writer and director Jason Stefaniak uses the art of storytelling to help others make sense of the complicated world in which we live. Find more about his work on www.jasonstefaniak.com and watch his shorts on SynopsiTV.